GRAFF

INFO

GRAFF

BIOGRAPHY

Antoine Graff’s destiny was not “folded” from the start. Of course, born a painter’s son and grandson of a blacksmith, it was inevitable that the arts would have an effect on him. Not to mention he has a surname which sounds like a pseudonym! Yet his career panned out a bit differently, between colouring, adventuring, and paper folding.

Antoine started to paint at the age of 8. At 14, the age when adolescents typically begin their teenage crises, he received his first commission! In 1954, he left his native Alsace and started studying fine arts in Paris, but primarily cut classes. His instinct encouraged him to visit the studios of artists Zadkine and Lhote. Zadkine, a sculptor, liked the feet of Graff’s statues. The painter Lhote considered him to be an excellent illustrator, once he abandoned Delacroix! Graff was trained by these two masters, and good ones at that! Surely an umpteenth tomfoolery.

His real adolescent crisis came at the age of 26, as he thought he was no longer “skilled.” It was a period of emptiness, when the homo habilis engaged in a fiery war against himself. Yet the biggest paradox is that this time allowed him to produce his work, supported by these his two gallery owners art dealers. However, nothing came of it.

He created a prestigious business of window displays for pharmacies that would make any seasoned businessman envious. The patent that he filed brought him 11 thousand pharmacy clients on a plate! But the homo habilis was not content with window displays. Instead, Graff took up print advertising. His expertise soon attracted artists. Télémaque, Arman, César, and Villeglé all lined up in his new back room to have their original prints produced. His business gradually evolved from printing to art publishing. He acknowledged it not nostalgically, but with an assertively humorous sense of perspective. His wealth grew, he travelled, and money was easy. Then came the ultimate stroke of genius: he was given the luxury of creating the gallery La Main Blue in Strasbourg, where he held exhibitions for Alechinsky, Bram van Velde and even Télémaque. For five years, he had his ideal project; tinkering in art.

The 1980s approached with its eccentricities of all kinds. Graff couldn’t restrain himself; “I’m just clowning around!” he declared. In reality, this zany statement didn’t fully express his particular state of mind.

He was looking for his “subject”, going so far as to draw strange hyper-realist compositions based on old family photos. It had the appeal of an ‘80s kaleidoscope. Yet after one failure, it goes without saying, he stopped everything; forget preserving legacies and all that fuss! Heritage was not really his cup of tea.

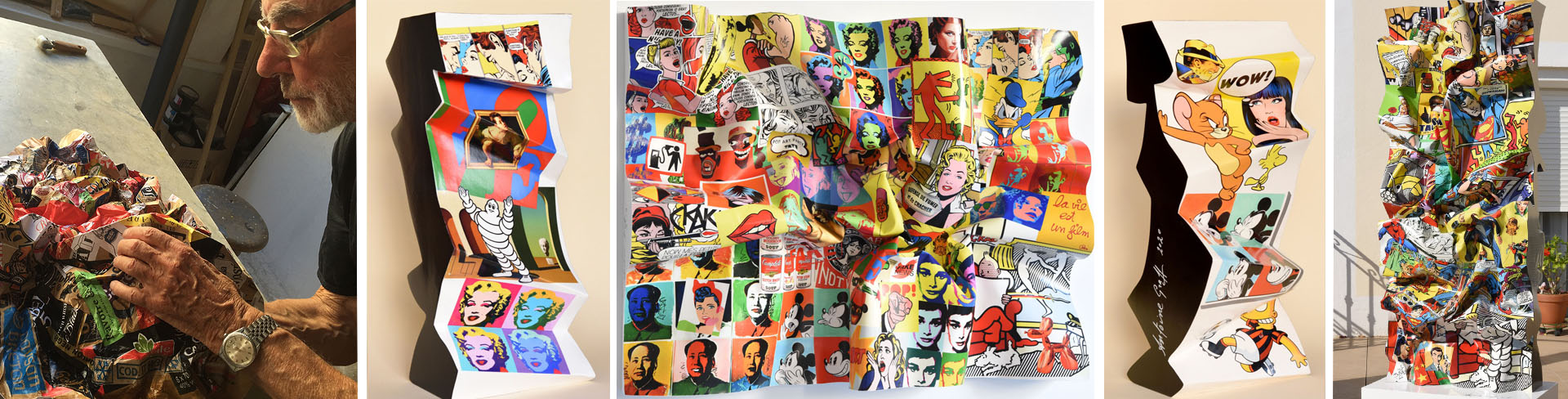

One morning at breakfast, depressed and distracted, he finally had a revelation. It was the paper wrapper covering his slab of butter, destined to be spread on his toast, which crinkled in extravagant, tangible, and poetic folds. Yet, he would need 4 to 5 years to discover what he could take from this vision to satisfy his new state of being. Antoine wanted to return to the source. He didn’t want to be skilled, he simply wanted to make, to create.

It was a bit of jazz that would help him. Graff, who had grown up with classical music, was now guided by the circulating rhythms of jazz, that soulful music. And it was through this music, in it, and in its name that he finally gave in to “his” discipline. The score was ready. He was going to play it, to infinitely deploy it.

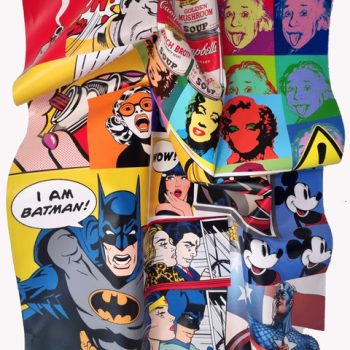

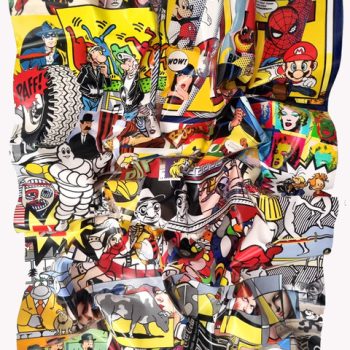

Crumpling and smoothing out, the fold is his toy, which he manipulates, twists and shakes—a playful experiment. But does his subconscious need to express itself by taking refuge in the cracks, in protective valleys? The Homo Faber needs to protect himself from human attacks, and in his work, this Hyrcanian folding was paramount. A man from the east, an Alsatian influenced by the valleys and other mountain formations, Antoine structures, models, and solidifies his material by creasing it, reliving the huge upheavals of prehistory, erosion, cracks, accidents, and excavations. His game from then on became tectonic, subterranean. The result is on the surface, but the foundations are always in flux.

He enjoys speaking about the random nature of folds, the imminent moment where the sequence is put in place. His philosophy, if one could call it that, is profound and his practice—that of the craftsman—counters physical and pictorial eloquence. There is no message, no figurative representation and no abstraction.

His motto is very simple: “The presence of wrinkled paper, that’s all.”